Teresa Urrea “Santa Teresa de Cabora”

“Saint Cabora”, featured on our co-ferment label, was a historic healer who practiced in Mexico and California and brought magic to the everyday.

Taken from Boyle Heights History Blog:

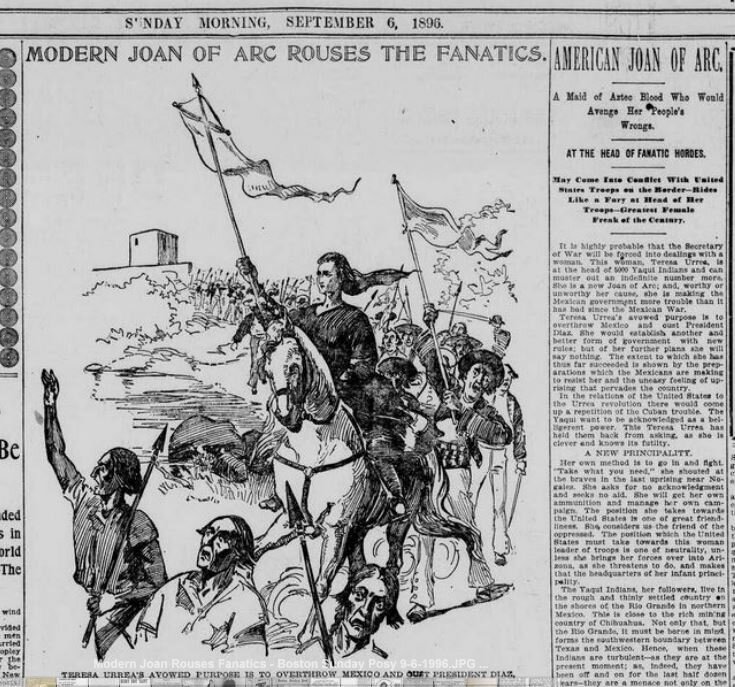

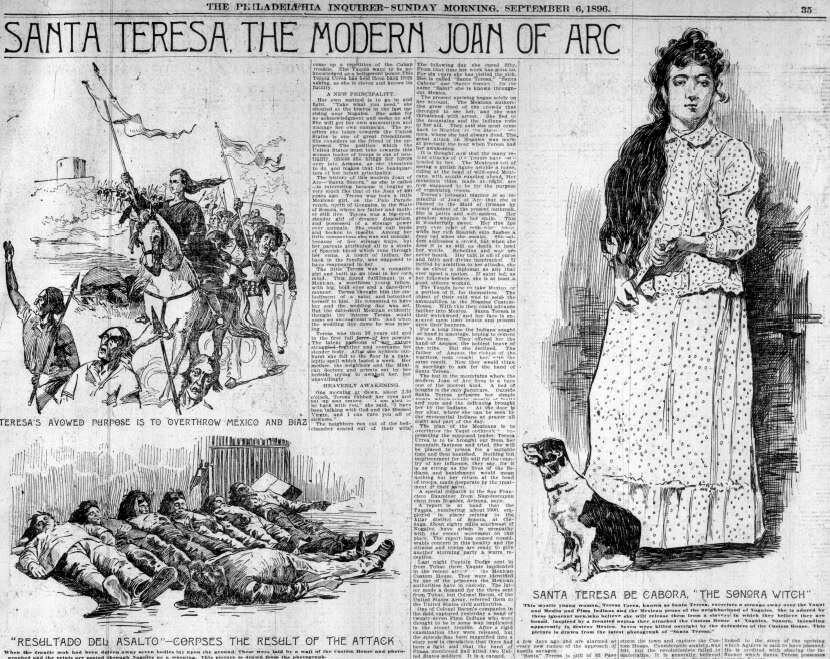

Boyle Heights Historical Society Advisory Board member Rudy Martinez has again provided another remarkable aspect of Boyle Heights history with this two-part post, including a postscript, on the amazing life of Teresa Urrea (1873-1906), known as Santa Teresa de Cabora. Famed for her involvement in events with Indians in the Mexican state of Sonora and with followers of hers in Nogales, Mexico, Santa Teresa toured America, including stops in New York and San Francisco, before settling briefly in Boyle Heights in 1902-1903. This first part looks at her life until coming to Los Angeles.

On October 30, 1902, the Los Angeles Times published a brief article with the headline, “SANTA TERESA APPEARS ON THE SCENE,” describing her as a “Girl Messiah who made a sensation in old Mexico” and now living in East Los Angeles. The article also reported the “young Mexican girl” was overwhelmed by visitors at her home “on the other side of the river,” while further suggesting that they were looking for her to be “healed.” But the article hardly explored the fact that there was much more to this young woman’s exceptional life before her remarkable journey brought her to Boyle Heights in the fall of 1902, where she lived in a small house at the corner of State Street and Brooklyn Avenue (now Avenida César Chávez).

Although only marginally known today, Mexican born Teresa Urrea (1873 – 1906), who was mostly identified as Santa Teresa de Cabora, was one of the most widely followed and charismatic figures of her time. Revered as a saint by the indigenous and the poor (but not by the Catholic Church) and exiled from Mexico as a political insurrectionist before she was twenty, she lived most of her adult life in the United States. The subject of a number of books, (two written while she was living), the public today may be more familiar with her through the “novelization” of her incredible and complex, yet short, life in two well-received bestsellers, The Hummingbird’s Daughter (2005) and Queen of America (2011), by Pulitzer Prize finalist, and her great-nephew, Luis Urrea.

Nevertheless, the story of Santa Teresa de Cabora, and especially the eventful period she spent in Boyle Heights, is little-known today, and in fact, only briefly covered in Urrea’s novels. So before examining that period, it might be helpful to the reader to first highlight the crucial events of her life before she came to Los Angeles.

María Rebecca Chavez was born on October 15, 1873 in Sinaloa Mexico to Tomás Urrea, a thirty-five-year-old hacendado and fourteen-year-old Cayetana Chavez, a Tehueco Indian who worked as a domestic servant. A staunch critic of the autocratic rule of the Porfirio Díaz regime, Tomás Urrea fled government reprisals in 1880 and moved his ranch operations to Cabora, in the neighboring state of Sonora.

When María was fifteen years-old Don Tomás finally recognized her as his own daughter, moving her into the family home where she took the name, Teresa Urrea. She also developed a close relationship with the elderly ranch curandera named, Huila, who was soon mentoring her eager young student in traditional folk healing and midwifery.

In 1889, possibly after experiencing a violent sexual assault, Teresa suffered a seizure and then quickly lapsed into a coma. After two weeks, Don Tomás ordered a coffin built, and a rosary be held around the clock until her seemingly impending death. However, during the rosary, Teresa sat up suddenly and said, “I will not be buried in the coffin, but you will need it in three days.” Three days later, Huila was found dead in her room. Teresa remained in a trance-like state for another month before she fully recovered and told those around her the Virgin Mary had appeared to her saying Teresa must use her “healing touch” to help the suffering poor.

By late 1891, as word spread about the young “healer” who accepted nothing in

return, a bustling community of almost a thousand fervent believers routinely camped outside the Cabora Ranch gates, with Teresa seeing two to three hundred visitors a day. While Teresa refrained from sermonizing to the growing crowds, she did openly proclaim that church intermediaries were not needed to converse directly with God. She also expressed her disdain about the amount of money the church extracted from the poor. Considering this heresy, the local clergy called her healing ministry “the work of Satan,” and denounced anyone who believed she was divinely blessed.

One firm believer was family friend, Lauro Aguirre, another landowner and Díaz critic. After moving to the southwestern United States in 1892, Aguirre published several newspapers advocating the overthrow of the Díaz government while also covertly organizing and funding several armed insurgent campaigns along U.S./Mexican border in the years leading up to the Mexican revolution. He also came to view Teresa as an effective symbol for armed resistance.

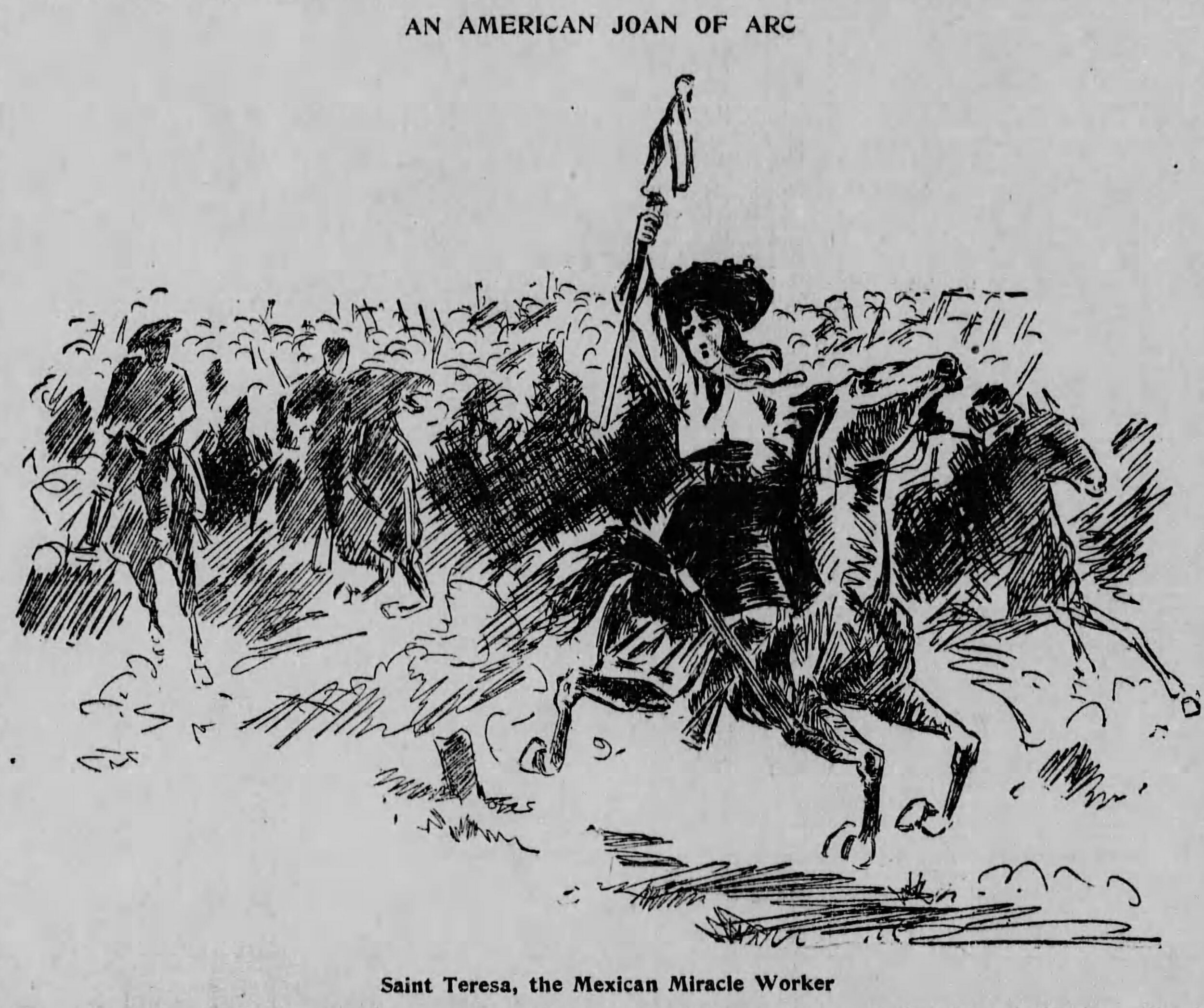

As Santa Teresa fanaticism was spreading during the early 1890s, the Díaz government was undertaking an aggressive campaign to encourage generous foreign investment while also confiscating large parcels of land belonging to the long-exploited Indians of northern Mexico and crushing any kind of resistance. Soon, many Yaqui and Mayo Indians began to view the young, “Santa Teresa de Cabora,” as a symbol of liberation. In 1892, 200 Mayo Indians stormed the nearby town of Navojoa, killing several federal troops as the cry of “Viva Santa Teresa” was heard for the first time. There was no evidence of Teresa’s involvement, but the Mexican government strongly suspected she was now using her growing influence to encourage open rebellion among her followers. Federal troops soon arrived at the Cabora ranch to arrest the nineteen-year-old for acts of sedition.

Seeking to avoid a larger uprising if she faced a firing squad, Mexican authorities exiled Teresa to the United States, along with her father. They arrived in Nogales, Arizona on July 5, 1892. By coincidence, their newly radicalized family friend Aguirre also arrived in Nogales about the same time.

An event that signified Teresimo as a resistance movement in prerevolution Mexico occurred in December 1892 after a thousand federal troops invaded the Yaqui village of Tomochic, in Chihuahua. Yelling, “Viva Teresita” as they mounted a counter-attack, the few-hundred armed Tomochitecos in the village were massacred by the government’s forces. Afterwards, troops discovered many of the dead were carrying escapularios that signified their allegiance to Santa Teresa. The massacre also inspired the narrative ballad El Corrido de Tomochic, cited as the first corrido of the Mexican revolution.

In early 1896, Don Tomás and Teresa decided to move to El Paso, Texas where their friend, Aguirre was publishing the anti-Diaz newspaper El Independiente. One day Aguirre took a photograph of Teresa, and later printed dozens of postcard-like prints. On August 13, 1896, sixty, armed Yaqui Indians operating in Arizona crossed the border into Mexico and attacked the customs house in Nogales while shouting, “Viva Santa Teresa.” Two guards and seven rebels were killed before the attack collapsed. Mexican authorities later discovered that each of the dead insurrectionists carried one of Aguirre’s prints of Teresa. Fearing possible arrest and extradition back to Mexico, Don Tomás and Teresa left El Paso in September 1896 and retreated to the remote eastern Arizona mining town of Clifton.

When Teresa resumed her healing ministry in Clifton, local physician Dr. L. A. Burtch was a frequent visitor who was impressed by the seemingly positive responses to her “healing hands.” Soon, Clifton’s white citizens began seeking her services, including the local banker C. P. Rosencrans, who brought his six-year old son. Partially paralyzed, his son reportedly showed marked improvement within weeks. Teresa was soon a popular and frequent guest of Clifton’s elite white society, becoming particularly close to the family of Juana Van Order, a Mexican woman married to a British mine owner.

On June 22, 1900, Teresa married mine laborer Guadalupe Rodriguez over the furious objections of Don Tomás. The day after they were married, Rodriguez took her to the train station and demanded that she return with him back to Mexico. Noticing her distress, the sheriff and a group of citizens intervened. Armed with a pistol, Rodriguez fired a few rounds and escaped, but a posse arrested him later that same day. However, the entire episode left Don Tomás deeply bitter, permanently damaging his relationship with his daughter.

In July 1900, Teresa left Clifton to travel to San Jose, California with Mrs. C. P. Rosencrans in order to treat her friend’s gravely ill young son, Alvin Fessler. After a few weeks, his health greatly improved, and within days, several bay area dailies published full-page stories about the “celebrated Mexican healer.” Shortly thereafter, a newly formed medical consortium offered to sponsor Teresa on a national “healing tour,” beginning in early September. Although the company stressed there would be no charge to individuals for her healing services, they reportedly charged all visitors a hefty “entrance fee” without her knowledge.

The tour left San Francisco in January 1901 and headed directly to St. Louis, Missouri, with plans to leave for New York City two months later. While in St. Louis, Teresa wrote to her Clifton friend, Juana Van Order, lamenting about her isolation. Juana immediately sent nineteen-year-old John Van Order, the younger of her two bilingual sons, to accompany Teresa as an interpreter for the rest of the tour.

Shortly after her arrival, the New York Journal declared on March 3, “Santa Teresa, the Fanatical Mexican ‘Miracle Worker’ in New York,” and dedicated an entire page, with photographs, to her arrival. Again, Teresa was soon the darling, or pet, of elite white society, a frequent guest at their favorite restaurants and tony brownstones. Stylishly dressed and coiffed thanks to her public relations minded tour sponsors, Teresa looked more like a Gibson Girl then the humble Mexican healer from Sonora.

She and John Van Order had also become a couple, claiming they were married, although Teresa had not yet divorced Guadalupe Rodriguez. On February 15, 1902, Teresa gave birth to their daughter, Laura Van Order, naming her after her friend and indefatigable newspaper publisher, Lauro Aguirre.

On September 22, 1902, Teresa received the news that her father, Don Tomás had passed away in Clifton, Arizona. Soon thereafter, Teresa decided to sever her relationship with the medical company and travel directly to Los Angeles. Apparently, Teresa’s primary aim in California was to obtain a divorce as quickly as possible from her then imprisoned husband, Guadalupe Rodriguez.

Follow Boyle Heights History Blog for more on Teresa.